Margaret Bullock’s new book “New Deal Art in the Northwest: The WPA and Beyond” is the first comprehensive study of this chapter of United States political and arts history. She and Douglas Detrick talked about how the programs worked and what they produced, how they affected communities, and how our community’s response to the COVID-19 crisis will be similar, and how it could be different.

The book is available from the publisher University of Washington Press, the Tacoma Art Museum store, Amazon, and Barnes & Noble.

Episode Transcript

Welcome to More Devotedly, a podcast for people who see the arts as a force for positive progressive change. I’m Douglas Detrick.

This is Volume III of More Devotedly, and we’re looking at how artists are responding to the coronavirus pandemic. The United States now has by far the most documented cases of COVID-19 compared to any country in the world, and now over 22 million Americans have filed for unemployment insurance. Fortunately, we are beginning to see the rate of new infections plateau. This is really positive news, but we have a long way to go before we can think of this crisis as over.

I interviewed my guest, Margaret Bullock, Interim Chief Curator and Curator of Collections and Special Exhibitions at the Tacoma Art Museum, just after Washington governor Jay Inslee ordered businesses closed. It was early in the crisis, though in reality, not much has changed several weeks later. We’re still completely in the dark about how long this will last, and what damage will be done to our lives and livelihoods.

Margaret’s new book “New Deal Art in the Northwest: The WPA and Beyond” is the first comprehensive look at what the New Deal arts programs looked in the Pacific Northwest, how they affected arts communities here, and how the programs compare to the arts funding structures we have in place today.

If you aren’t familiar with the New Deal, I encourage you to look up some trustworthy information, but in brief, the New Deal was a numerous and diverse group of programs and legislation launched by the Franklin Roosevelt administration beginning in 1933 as a way to put unemployed Americans back to work during the Great Depression.

As Margaret says in the interview, there were very few professional artists in the 1930’s compared to today. The arts weren’t considered by most people to be legitimate work at that time. However, several arts programs were launched to employ artists of all disciplines. The programs launched the careers of many artists, and lent a new legitimacy to their work. And thankfully, the artists of the New Deal, like photographer Dorothea Lange gave us an incredible body of documentation of this time of crisis in the United States. Artists played an incredibly consequential role in helping us understand and give meaning to what could otherwise seem like a senseless tragedy for generations of Americans since.

And it was a time that the federal government played a pivotal role as well. The New Deal art programs succeeded in many of their goals, like employing people with artistic backgrounds, preserving their skills, and giving Americans access to arts experiences in their everyday lives in their own communities. But it fell short in some important ways as well, since the programs often excluded artists of color despite those artists having great need.

Unemployment during the Great Depression peaked at above 20%. We don’t have official unemployment numbers for April yet, but the 22 million Americans who filed for unemployment so far constitute about 13% of the workforce. And some economists predict that unemployment could go as high as 25% in the months to come. We’re on the brink of what could be the worst employment crisis ever to hit the United States and the only thing that I think we can be sure of at this point is that this country will not emerge unchanged.

But how will we change? The New Deal and the legislative innovation that made it possible can teach us some lessons for the kind of change we need now. In some ways, the New Deal was a blunt instrument. In 2020, we could do a more efficient job of putting money in the hands of people who need it. But in terms of the raw money that needs to be injected into the economy right now, we don’t just need a New Deal, we need three of them, or more. A decisive, pro-active response from the government will be critical.

Margaret and I talk about the New Deal arts programs during the Great Depression, and how the recovery from our current crisis will look different, but how the arts will still play a vital role in documenting the pandemic, and in imagining a better future after it’s over.

Here’s the interview.

Transcript

Doug Detrick: how are you doing Margaret?

Margaret Bullock: I’m pretty much doing like everybody. There’s moments where I feel I’m okay and then I get really kind of disoriented and, I would really love to, like everyone, know when it’s, when it’s over. you know, even if it’s a ways out, you know, so that sort of thing. But trying to keep busy and keep things moving and stay sane like everybody else.

Doug Detrick: That’s exactly how I feel. I really just wished that I knew when things were going to be over, you know.

Margaret Bullock: We’ve been trying to do all of this contingency planning, but you know, it’s impossible. It’s sort of like, well, it’s a two month, three month, four month, five month closure. It’s really hard to tell how to plan, you know, what are you planning for within the landmarks of course shift, radically depending on which version you’re looking at. So I think everybody’s trying to get some control over it that way.

Doug Detrick: Yeah, of course. That’s the one thing we don’t have. so Tacoma art museum has been closed for a little while. What have you seen about how people in the arts community kind of more broadly, you know, and that can be just art supporters, artists themselves, how are you seeing this community respond to this situation?

Margaret Bullock: Well, I suspect it’s like everywhere. There’s a lot of variety, but I’m here, you know, it hit us pretty hard, pretty quickly, early on for the U S in Seattle in particular. I was amazed with the speed with which a number of the local and state arts organizations started responding.

It was almost immediate in terms of changing up the ways they were handling grants or offering different support programs for artists or just to get money into the hands of institutions so that they could pay their staffs or continue their grant funding. So that’s been amazing to see. it’s also, of course, lots and lots of people suddenly in a world of hurt, lots of artists, as you know, well live sort of day to day and job to job and have multiple jobs going or multiple gigs lined up and they’re just seeing cancellation after cancellation.

So. they too are struggling with that sort of, when does it end? How long does this go on? And, what does this mean for me going forward? I’ve seen a number of wonderful online things happening though to people just trying to keep creating and keep that energy going. despite this crisis.

Part I

Doug Detrick: since you have spent all this time focused on the visual art that was happening as part of the new deal, could you kind of give us an outline of the projects that were funded and what kinds of things were they, and when was this happening?

Margaret Bullock: Sure. So there were four programs for the arts, for the visual arts in particular, and they’re government programs, so they love acronyms of all kinds. So they all have initials and they all sort of sound the same. So the first one was called the public works of art project, or the PWAP.

And, that was really a short term pilot project that was just to see could this work and how might it work? And it was started right at the end of 1933 in December of 1933. And the idea was really just to get money into the hands of artists as quickly as possible. So some of the initiatives were simply to go to an artist and ask to buy something in their studio that was already done or something they were almost finished with.

But then there were also commissions for specific works. Artists hired onto projects where you might not expect them to be. For example, say the highway department was building a new road. They’d have an artist designed the new road signs, you know, anything that he could do to sort of get the money out there.

And it’s amazing how fast it’s they authorize the program and literally the next day there are people working in hiring artists to work. It was incredible how fast they were able to get it to go. And it runs for just under five months or so. It ends around April, beginning of may of 1934.

And it’s so successful, they go ahead and almost immediately decide on another program, and there’s two that kind of run parallel and end up merging together. So, there’s one called the treasury relief art project, or the TRAP of, it’s usually called kind of generally. and that one was specifically for the decoration of public buildings.

There was a lot of construction of new post offices and courthouses and government office buildings as part of the new deal programs. And so this was really the origin of that idea of the 1% for art allotment that you would take 1% of your construction budget and use it to put artwork in a building.

So a lot of those artworks under the TRAP go into courthouses and post offices and things like that. And that one starts pretty quickly, in 1934 and then runs, for a couple of years and ends up merged with this bigger one called the Section of Fine Arts. And the section of fine arts is also a program to decorate government buildings, though on a bigger scope.

And it starts in the fall of 1934 and runs all the way into 1942. And that one ends up kind of eating the treasury relief art project cause it’s bigger and more widespread. And it’s a fascinating one because it’s really about government deciding what those images will look like. This is the project where the government has the most control over content.

So they organize these committees that send out calls for competitions, for post offices in other buildings, and then decide which artist is going to do the work and then work with them, down to the finest detail on what that final artwork will look like.

And then finally the last and best known of the projects is the federal art project under the works progress administration. The shorthand for all of these, most people just call it WPA art, just to keep it simple. But, this starts in August in 1935 and then runs into, February of 1943. And it really was designed to just put anyone they could find to work that had an artistic background. So the scope of the projects is huge and the variety of the work is really amazing.

Doug Detrick: Are there some examples that you can think of that people might just know from being just aware, and not necessarily art historians or anything like that?

Margaret Bullock: Yeah. I think if you’ve been to Washington DC ever then all over downtown, particularly along Pennsylvania Avenue and all of those government buildings. Many of the sculptures, and other artworks along just along the street down there are from the new deal art projects. Also a lot of the government buildings you can go into in Washington DC if you see a mural or a sculpture, often those are from the projects. And then if you’re kind of talking West coast where we are probably the most famous and well known out here is the Coit tower in San Francisco.

Doug Detrick: as an Oregonian, I’m, even more familiar with the Timberline lodge, which is probably something that a lot of folks will remember. So it’s a ski lodge that was built kind of near the treeline on Mount hood.

Margaret Bullock: I’m glad you brought that up cause that is really the shining star of the projects, not just out here in the Northwest, but really nationally. The whole thing was a project under the WPA and mostly under the care of the art project in particular in Oregon.

So every part of it, the furniture, the wrought iron doors, the carved banisters, the bedspreads, everything in there was made by artists working on the art project in Oregon. It’s, it’s incredible. And like you say, a living museum now that millions of people go to see every year, so you can kind of really step completely back into that era and get fully immersed in it there.

Doug Detrick: Neither of us is an expert on, you know, federal arts funding necessarily down to maybe a really detailed level, but I wanted to ask you a bit about new deal arts funding, how does that compare to the level of federal arts funding that is in effect now.

Margaret Bullock: I’m an art historian, so I’m always afraid of trying to do that math, but I know that all told the new deal art projects spend about 39 million on them, there in the 1930s, so with inflation and all the math today, to get it to today’s dollars I don’t know what that adds up to, but, you know, I think the NEH and the NEA are nowhere near those levels of funding, just those individual agencies. So definitely in terms of the overall budget for the federal government during those years, it was a much, much higher percentage.

Nowadays we have all these other arts organizations at the state and local level that do a lot of the same sort of work in terms of grant funding and supporting artists. So it’s also a different, more sophisticated equation now I think. But, in terms of the federal government specifically it’s definitely not at the same levels at this moment in time.

Doug Detrick: And then are there some notable artists, maybe both on a national level and maybe somebody who is more tied to the Pacific Northwest, but is there an artist you can think of who’s work for the new deal era programs was really important to their career.

Margaret Bullock: Yeah. There’s two major examples out here in the Northwest. I mean, there’s lots of them across the U S because it was just a really key moment in time. You gotta remember this moment in time, this sort of gallery system that we’re used to now and the museum system that is part of the ways artists get employed and get known nowadays was not really the same at all at that period of time.

A number of artists get their start through these projects. But out here in the Northwest, there’s two in particular that I think people would know. For Oregon, it’s the photographer minor white. He was, you know, he became one of the great photographers of the 20th century. He’s one of the great modernist photographers, but he got his start there on the art project in Portland.

And he was hired first just to take documentary photos of what was happening on the various WPA projects around town, and then began doing creative work, which they supported as well. And so he really starts his career as a fine art photographer working on the art project in Oregon. And he talks in his own interviews and later in life he talked about how important it was that he had that job and got that opportunity in that moment in his life when he was figuring out what he wanted to do.

And then up here in Washington state, but also nationally. I think probably the best known name is Morris Graves, who’s one of that group that’s called the Northwest Mystics that are so well known for the Northwest from the 1950s but all three of the four of them worked on the art project in Washington.

But Morris graves, in particularly, this was his first real job as an artist. In the work in the archives, I actually came across a letter where he was being introduced, which was amazing to be reading along. It’s like, “you should give a job to this young artist who I think has great promise, and his name is Morris graves.”

And I kind of fell out of my chair in the national archives is like, what are you artist of great promise. It was just funny to come across him just walking into the, into the scene as it were, and that moment in time.

Doug Detrick: Yeah. So it sounds like it was definitely a really important stepping stone.

Margaret Bullock: He got a chance to, to work, to get to know other artists and look at their work, to hear critiques of what he was doing. And, the show we have at the museum, we have a really early work by him from one of the first projects. You can see already where he’s heading, but it’s also early days for him. So it’s really great to see that, you know, our own collection has a number of works by him, but for much later in his career. So to see that early step is really, really fascinating.

Part II

Doug Detrick: How did these programs expand access, both for the audience and then also for the artists themselves. Would you say that, what are the goals of the programs was to expand access to the arts for the audience?

Margaret Bullock: it’s interesting because the projects have this sort of dialogue or struggle. Going on the whole time, which is that half of the people that are organizing them and advocating for them, just see them as a way to get money and jobs out there into this economy and try to restore it.

And then there’s this whole other group who have these higher aspirations, which is that they really believe that art is as essential to daily life as food and shelter, and they want to make sure that everyone has access to it in some form and can experience it. So whether that’s seeing it or making their own, or hearing a lecture about it, or seeing an exhibition, they just want to make sure it’s widespread.

And they also recognize how powerful it can be in, in terms of telling stories and delivering messages and kind of pulling a shared culture together really helps pull a nation together in difficult times. And so they see the power and potential in that. and it’s as back and forth all through the history of the projects when you look at what they’re funding, when they’re funding it, who’s making arguments about whether to take the money away and put it elsewhere or to keep it. That’s one of those threads running underneath is that purpose.

And certainly, like I just touched upon a minute ago, there wasn’t the same system of galleries and all of that that we’re used to now. We’re so used to Thursday night art walks and things like that where you can go wander in and out of all these spaces and see art, and that just wasn’t common then. And so to have suddenly these places where you could go and see art in your everyday life, maybe it’s just on your way to go mail a letter, pay your taxes or pay your utility bill, you would encounter this artwork was really a different, different idea.

Doug Detrick: It seems like there was a kind of a constant struggle between people saying like, well, we don’t, want these people spreading, you know, leftist ideas, or we, we want them to do things that are a little bit more safe in terms of the content. you know, how did you see that playing out?

Margaret Bullock: Well, it’s really varies by what project you’re talking about and which state you’re in and even often which city you are in. And that’s where I found it really fascinating was how complicated it was. So there’s a sort of easy back and forth at the top, at the federal level. Where there’s one party in charge who’s loving it and the other party that hates it. And slowly as the power shifts, so does the funding.

So the two projects I talked about for the murals and sculptures for government buildings, those were really carefully controlled as to subject. Artists were encouraged to particularly stick to images they called the “American scene,” which was scenes of daily life, and maybe going back to pioneer stories or celebrating the industry of a town or its natural resources or something like that.

The committees that oversaw those actually got into the details all the way down to the simplest thing. So I definitely saw letters and correspondence in the files where they’d ask people to change an artist’s expression, for example, because they thought the laborer looked too angry and they were worried about what that might mean or, they thought that the tone of the pallet was too dark and that people would find it depressing so they asked them to lighten up the colors.

But on the other two projects, particularly the federal art project under the WPA, there is so much happening in so many directions that there was just no way to control it in that way. And it really was about just doing it as broadly as they possibly could.

Whether your motive was jobs or your motive was, kind of shared national culture. It was so big that it was hard to control. I could see moments, in particular projects in the Northwest where maybe an administrator got in the way for a while or argued against a particular commission. But for the most part, there’s not a lot of interference.

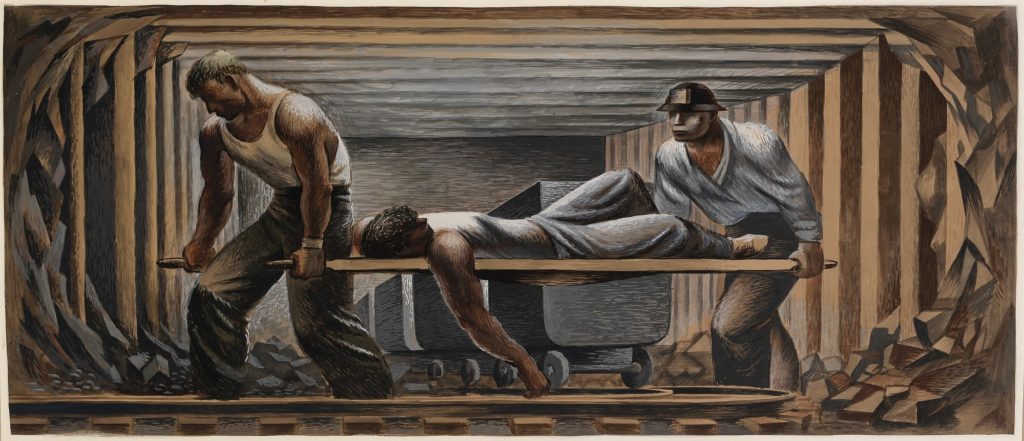

Doug Detrick: I remember there’s one example from the book where, it was going to be a mural in a building. Um, and it’s an image in a mine. There’s one minor who’s been injured and he’s being carried out on a stretcher by two other minors. hopefully I’m not wrong about this, but then it was, it was changed. Is that true?

Margaret Bullock: Yeah, you got it absolutely right. That post office in Kellogg, Idaho, the artist is Fletcher Martin, and his original plan was to do an image of an accident in the mine. And when local people saw it, and particularly the miner’s unions there, everybody was very pleased. But then the chamber of commerce got hold of it. And the local Congressman. And they didn’t want an image like that in the post office that was showing the problems of mining and the hazards of mining. And so they forced the artists to change his subject. It’s really sad because the study’s really strong and a really fascinating image. And you can tell that his new version, he wasn’t as committed to. So he did an image that just shows the discovery of the mind that led to the founding of Kellogg. But it’s not his necessarily his best effort, we’ll say.

Doug Detrick: I agree. Well, I mean, you know, my personal taste is my personal taste, but I agree that I like the original image much better. I think it’s more striking and memorable to me. Just reading that story in the book was obviously one of the things that really stuck out to me as a showing that political struggle, you know, between different groups of people, even just in a small community like Kellogg.

Margaret Bullock: Yeah. And it was interesting to me who was for it and who wasn’t. I knew that there had been a controversy. But I, it wasn’t until I got into the archives that I saw this sort of back and forth, and I assumed it would be the miners unions that were protesting that they wouldn’t want that image shown and it was completely different. It was the companies in charge of the mines and the local chamber of commerce and things like that, not miners, they were happy to see the sort of reality of their everyday life up there, which was fascinating to me.

Doug Detrick: I suppose that the mine owners might want to pretend that, everything is always nice and pleasant down in the mines.

Margaret Bullock: Yeah. And it’s, it’s strange to me, some of them, you know, that the subjects that are chosen. I went to visit most of them while I was doing the work for this book and exhibition and the sort of things that are considered. I mean, a lot of them were exactly what to expect, but there are others you walk in and it’s just startling what the choice was, and you think, I don’t know if I’d want to, if this was my regular post office, if I would want to be encountering that every time I, walked in here and that’s one of them. You know where I can see where a mine accident, you would think, huh, people might not want that, but instead the community was supportive of it.

Part III

Doug Detrick: Well, why don’t we change our focus a little bit to talk about the artists, themselves and how this idea of access affected their access to opportunity. You know, I think one of the things that’s really important about when we’re talking about history, is that we look back from 2020, and we see things the way we think of them now. And you know, that example that you give of how, you know, now we have this pretty widespread system of museums and galleries, and there are also like municipal arts funding organizations. There are state arts funding, there’s federal arts funding. So like, you know, things are not the way they were, without knowing all that context, sometimes it’s hard to understand exactly why these programs were important and why people were putting them into place.

I think one of the ways that our field has changed in the last, I don’t know, decade, and certainly not always successful, but trying to be more supportive of a diverse and equitable and inclusive arts community. Yes, this was a broadly participatory set of programs. But it was not perfectly inclusive. How did they stack up in terms of being inclusive of all the artists who were working in the United States at that time?

Margaret Bullock: Yeah. Well, it’s, that’s a good question. It’s an, you know, there’s that issue too. And when we look back at history, we tend to get kind of rosy about things. And this is one of those areas where we get really nostalgic and rosy because of all this help that was given to people in a time of crisis and all this amazing artwork was made.

And we tend to kind of think of it as the best thing ever and not necessarily look at the details. And that’s where digging into it, started to kind of take some of the bloom off, for me because there is all of this talk, at every level of these programs and the administrators who run them about it being an opportunity for all so that everyone could see art make art.

And that artists could be employed. And certainly that is a really important thing for the artists who are employed. You see these letters, you hear these memoirs that have them talking about how critical it was, not only to get the job, but to have the government recognized that their work was real work that up until this moment in time, really the idea that you were going to have a professional career as an artist if you weren’t working commercially was really, you know, you just didn’t normally just be a painter and, and get along that way. And so to have the government say, this is legitimate work, this is the legitimate job you should get paid was amazing. And there are definitely, you can see. how hard they worked to a certain extent to get lots of people who were in need on the project.

So, there’s this interesting problem that in order to work for most of the projects, you had to be signed up for government relief. And you could at that moment in time, tell them your skills were whatever you chose to tell them, you didn’t have to prove anything. So lots of people would say they were artists and maybe they were a weekend hobbyist.

Maybe they were a professional or anywhere in between. So that gets someone off the relief roll and get them hired and then find out that they really weren’t professionally trained. But they find ways to keep them. So I remember that there was a story of this one woman who was elderly and who was just really, she’s absolutely starving to death, literally starving to death and had signed up as an artist and they hired her and then found out she couldn’t draw to save her life, but they, they managed to find her a job, which was doing, something like, I think she was creating labels for art books.

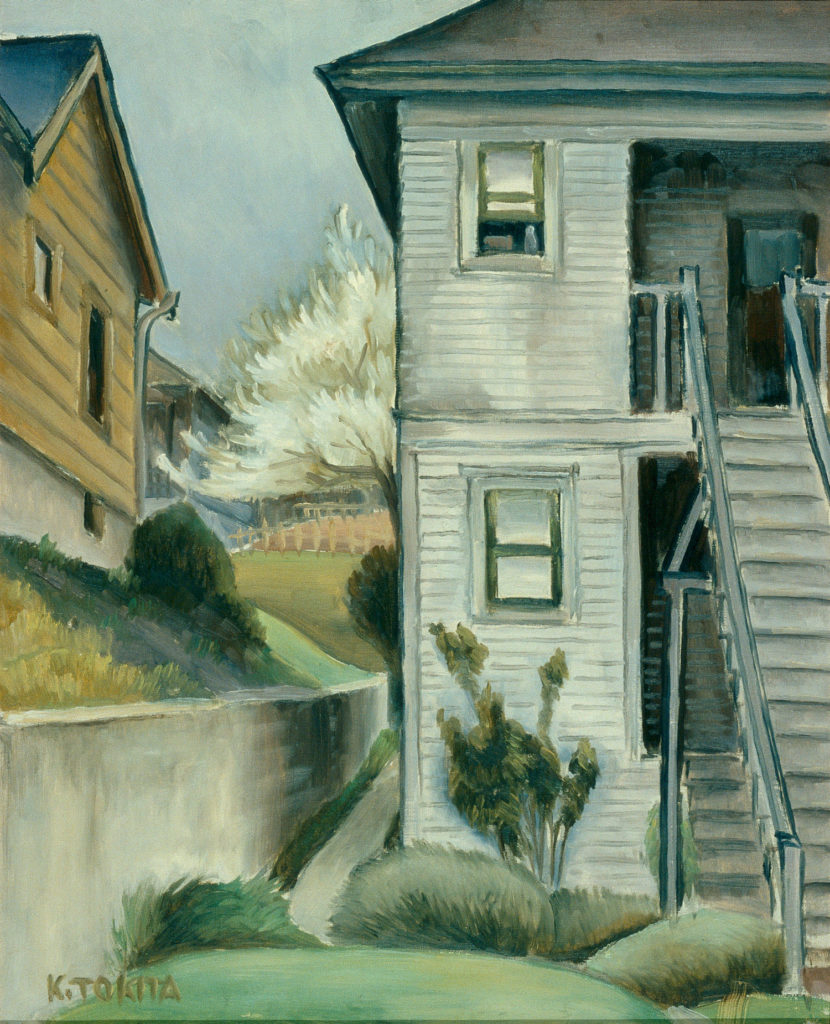

And so they really tried hard to stretch it to make sure that she got some support. But then also you really look, and you know, here in the Northwest, for example, we have these really strong, talented communities of artists of Asian descent here in the Northwest in the 30s who were really leading the way in a lot of ways, in terms of new modernist ideas, in art, in photography out here in particular.

And there are almost none of them employed on the projects out here. A few on the early project, the first project, but you get later down the line and there’s only one or two from this whole group that I know were here and most likely in need.

Countrywide and in the Northwest as well, African Americans were usually having to go to segregated art centers, often not employed at all or employed on lesser projects, and out here in the Northwest so far. I have a list of lots of names. I don’t know who they are yet, but so far I’ve only identified two African American artists employed on the projects out here in the Northwest.

And then native American artists. You see lots and lots and lots of post-office images and easel paintings and everything else of battles with native groups and settlers moving in on their land and sort of the cavalry victorious against them. But, no images really of the realities of that, of people being murdered and displaced or of native life being disrupted, or even their original origins on those lands.

So it’s rare to see native artists employed on the projects. There are a handful. And out here in the Northwest, there are four that I’ve identified so far. And one of the most amazing works here in the Northwest if you go to the Blackfoot. Idaho post office the mural was done by a young native artists and he actually was allowed to paint the entire lobby.

So it runs all through the lobby walls and into the lockbox lobby and their scenes of native life. And they’re in dramatic contrast to a lot of the others, which are, you know, native peoples, dying on cavalry attacks and things like that.

And I found it with like one of the situations I ran across this young artist I was just talking about. He painted the mural in Blackfoot and then people who were local who considered themselves, these were Anglo people who considered themselves specialists on the native life of the area, complained that he hadn’t painted it the way life really was for native people and wanted to change it.

And it’s like that whole sort of, he wasn’t allowed, you know, to have his own voice or to speak his own reality that others were going to tell him what that was, was really, you know, hard to see and to read. And I’m really glad that they did not allow them to change the mural as it stands. It’s an amazing thing.

Part IV

Doug Detrick: what is the state of this work now? Some of it is still in these post offices, I’m sure. And then some of it might be well preserved and some of it is not. I’m curious what you found in terms of how well this art is kind of holding up now and how accessible it still is, or is it scattered and forgotten.

Margaret Bullock: Someone was asking me the other day, before the Corona crisis, they were sort of saying, you know, should we do this again? Would you think that this would be a great thing for the, the U S to do again? And one of the problems I was talking about was, what do you do with all the art that was created because it was thousands and thousands of artworks. And the project ended really abruptly, so it’s all ticking along and doing great. and then the U S enters world war II and, almost overnight they shut down the art projects because all the government funding turns to the war machine.

And these offices are left, you know, with all these piles of artwork that belonged to the government that are supposed to be allocated out to tax supported institutions. And now there’s nobody there to deal with that, no place to store them, nobody to care for them. So there’s lots and lots of stories of artwork being thrown away, given away.

I’ve heard lots of stories, seen lots of stories of how works have been recovered since or saved. There are works quite a few that you can still see. We mapped out, for example, the post offices here in the Northwest where you can still go and see, and there were 39 done in the four States that were considered the Northwest in the projects.

And almost all of those are still in place and accessible or if the post office is no longer a post office, the artwork’s been moved and it’s still viewable. I have this list of something like 2,500 works, at least that were made in the Northwest, and I know where maybe a thousand of them are. So there’s thousands still missing just in our own region.

And condition wise, it wildly varies. I’ve seen post-office murals that are peeling off the wall, and I’ve seen others that have been treated like community treasures and well cared for. and then everything in between with the smaller scale works that are more portable, that have moved in and out of offices and storage lockers and things like that.

Doug Detrick: how did you become interested in this era? And you know, what got all the way to having just released a book about the topic, which is quite an accomplishment by the way. And it’s a very beautiful book.

Margaret Bullock: Oh, thank you. It’s kind of miraculous to me. Every time I pick it up. I can’t believe it’s actually done. I’m kind of embarrassed to say it was completely serendipity and I actually kinda didn’t want to do it when it all started. I used to work at the Portland art museum in Portland, Oregon. I was an assistant curator there when they landed a grant from the Henry Luce foundation to do some work on the American collection. The curator at the time decided to do three small brochures about aspects of the American collection.

And she did two of them, and then she assigned me the third one. And the museum had this large group, several hundred works that were from the federal art projects in their collection, and not a lot of other documentation about it, like where they had come from or why they were there. And so she just thought it would be nice for me to do that research and pull that information together.

I had done my graduate work on Winslow Homer and was really working in the late 19th century and the gilded age was my focus. I knew about the new deal and I knew what these projects were and sort of a general way, but it really wasn’t my area of interest. And I thought, well, okay, I, yeah, you know, it’s, it’ll be a good experience how you get into these things. And I started working on it. And for one, I just love research. So I found out pretty quickly, there wasn’t a lot on it, particularly in the Northwest. There was no central resource, there was no central place to go to. There were no lists of who did what or what was done. So that to me right there was really exciting.

The grant allowed me to go out to the national archives in DC and go into the original documents and things. And I started coming across these people’s stories and realizing the extent of it and just how varied and how huge this thing was and how complicated.

And that got me more interested. And then I ended up getting involved with a group of people there in Portland who were also interested in various aspects of it. And so through the help of the Oregon cultural heritage commission, we pulled together a symposium and a number of other things that talked about various aspects of the new deal and it just snowballed from there.

I would put it aside for a while. I get back to it. I’d put it aside. And then I left Oregon and ended up after several jobs here in Washington state. And one of the people who’ve been involved with me originally said, “Hey, you should get back to that WPA research and you should expand it to include the rest of The Northwest States that were involved.” And so I did, and it’s been sort of working its way that way. And thankfully I’d been working at an institution that found that interesting and thought it would be a really worthwhile project to support. So the book and the exhibition grew out of that, but it’s taken a really long time to get there.

I did want to say something too about, you were talking about community. Just to circle back to how you heard about these groups. You know, when I talk in these interviews about these projects, you know, I hear myself making all these generalizations about something that was so big and so complex and things get left out.

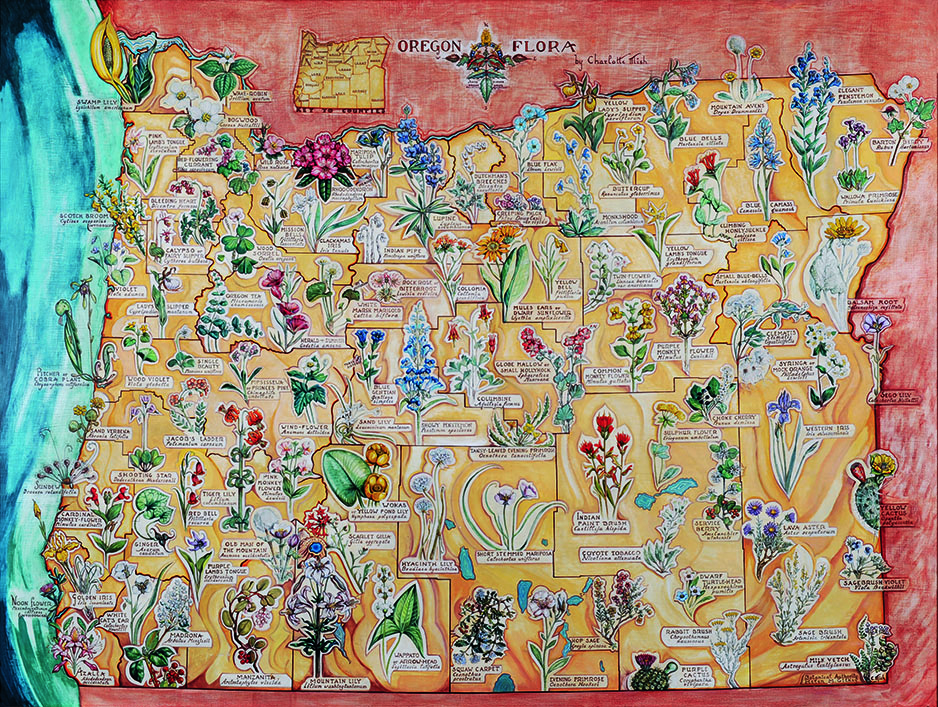

And one of the main points of the federal art project that I wanted to talk to just bring up is this idea of the community arts center. That was really fundamental to them, that idea that art should be accessible to everyone. And so they organize these art centers mostly in smaller towns that didn’t have Big resources. Some were in bigger cities, and you could go there and you could take a class for free. You could see an exhibition for free. You could make your own artwork, you could do all sorts of things, and through these community arts centers. And it was designed to make sure that people could have that access.

And it was incredible to me because the exhibitions they were circulating were amazing. So there’s like a Picasso show that was going to these art centers. You could go see it for free and you’re like, where in this world today can you go see a Picasso exhibition for free? So it was really an amazing thing.

And they required community buy in to set them up. So if a community wanted an art center, they had to provide a building where it could be, and then they had to fundraise enough to help pay for the utilities and the upkeep of the building. And then the government would provide the artists to teach and pay their salaries and provide the materials.

And so communities would have these incredible fund drives, where like the kids would donate their milk money and you know, people would do bake sales and all these incredible things in the depression to pull together this, you know, $150, $200 whatever they needed to start their art center. It was really an incredible movement.

Some of them survived. Of course, the war put an end to them and a few kind of sputtered back to life after and then couldn’t make it. But there are still some out there. The Bush Barn art center in Salem, for example, is the stepchild, I guess, or the kind of continuation of the Salem arts center.

Part V

Doug Detrick: As you and I are talking right now, the United States Senate has been debating just how they are going to provide some economic relief. But, you know, I think that the debate has been, should we be shoring up large companies and, and corporations or should we include, like, you know, people that are doing gig economy type work? and then small businesses as well. I can say for sure that here in Portland, and, you know, especially in our music community here, those small businesses are the most important parts of our arts economy here. All of the venues are owned by small businesses. if they are not able to survive this crisis, we could be looking at a situation where, you know, let’s say this summer, things are more or less back to normal. but normal means that we have half as many venues as we used to have.

Having done all this research about this period, and comparing the economic downturn that we’re likely to see as a result of the coronavirus outbreak with the great depression. How do you see the role of government funding in the arts? I’m kind of curious where you landed on that, or at least what are the questions you’re asking yourself that you think need to be answered.

Margaret Bullock: Well, I think, you know, for us nowadays, it’s an argument that arts organizations make all the time, and that is absolutely real. And it’s like. Part of a major part of the economy is the arts. And I know for us here in Tacoma, for example, it’s a big part of our city’s economic engine are the various arts here in town.

And so it’s, it’s fine to keep Boeing afloat. But what about all of these, like you’re saying, all of these smaller organizations that are actually the heart of our economy, part of the heart of our economy down here. I’m hoping because there’s a system already in place nowadays, all these state arts organizations and regional organizations, that they just move the money to those organizations because they know best who’s in need and how to get it out there fastest and already have those processes in place.

So to try and have it be yet another federal program, that isn’t in place yet, that they try to activate quickly, I think would be a mistake. But I’m seeing in the advocacy that we’re doing through various museum organizations in that I see some senators talking about is that idea of making sure the arts are involved in, in any of the programs that happened.

But yeah, I completely agree with you. It’s like, it’s, it’s the small, down at the grassroots level that needs the support, for the arts economy to keep rolling. it’s nice to keep all the bigger institutions going to and working at one of them. Of course. You know, we want to be able to reopen our doors as well, but there’s, there’s so much more that needs the help.

It’s interesting because one of the issues around the new deal in the arts programs then was people had this romantic idea of the starving artist, but this idea that you could work professionally as an artist really wasn’t something people thought universally and supported.

And so the idea that the government would see it as legitimate work and support it was really powerful. I think nowadays, we know people, lots and lots of people who make their career as artists, and we love that and we support them. But there is still a lot baked in, maybe subconsciously into our ways of thinking that it is a privilege that they’re allowed to live that way or something like that. I don’t know how best to phrase it, but still going back to that romantic notion of you should be having to suffer for your art, and how that tends to kind of direct things. And so I’m hoping that weird subconscious bias doesn’t get in the way of proper support and relief for artists as well.

Doug Detrick: A lot of us deal with that kind of poverty mindset of like, why would anyone pay me for my work? I’ve been talking to several people lately about how they’re trying to respond and how they’re moving forward during this time.

You know, and some of them were talking about, you know, it’s given me time to just kinda think about what I’m doing an evaluating how important it is to me, really. You know? And then some people are talking about how can I give back? .

I mean, we can think in the short term about how can I give back and how can I connect with people in a meaningful way during this time where lots of people are really in shock just about how fragile their lives were. I mean, I think that’s one thing that this crisis has exposed is that if there is some emergency, it means that folks who rely on a steady stream of gigs keeping them afloat, Pretty workable when times are good, and, times were pretty good until a couple of weeks ago. but then now, everybody’s in an emergency situation together.

but then it also kind of reminds us that even under normal circumstances, in a good economy, people have emergencies, they have health emergencies, they have, all kinds of things that can happen.

And there’s very little safety net, for them to rely on, especially folks that are self-employed. they’re working gigs there doing arts projects, and they don’t have that steady w2 paycheck that the government usually thinks about when they’re thinking about people that need relief. case in point, Donald Trump was talking you know, until recently, about a payroll tax holiday where that does nothing for anyone who’s not getting paid and who’s not a regular employee of a business.

So I think that this crisis has definitely exposed that. And it’s somewhat similar to what the new deal was addressing as well. Like, people that suddenly are desperate economically and need support, and the government can step in and it should.

Margaret Bullock: I had been seeing some interesting things to that I wonder if they’re helping or hurting. Like I saw this article the other day that supposed to inspire people to talk about what amazing things artists did under pressure. Shakespeare wrote his best works while the plague was raging and things like that.

And, and I understand the impulse, but I also worry about what it’s doing to artists who are struggling. It’s this crazy moment. And like you say, people are figuring out how fragile their way of living is. And, and there’s all these other stresses and anxiety. So to be expected to be inspired by the and be making important new work at this moment in time. You know, I worry about that too, that there’ll be some sort of standard that people are held to. I’m really concerned about the sorts of pressure being put on people that are already struggling hard, to be expected, to stay positive, to stay inspired and to make us all feel better because they’re the ones who normally do that.

Doug Detrick: Right? Yeah. There is that, tension between this idea where artists can through their work say things that can’t be said, to kind of heal people in a certain way. and I believe in that and I subscribed to that, but then I also. Agree with what you’re saying, that that’s also kind of an unreasonable expectation that we put on artists, that they are somehow resilient to all the anxiety that everybody is feeling right now, and that somehow we’re going to feel just magically good enough to, write that next song, or make that next painting at a time when all of us are feeling, very anxious about our own futures.

society does have very very high expectations of our, artistic community and at the same time, also expect them to be poor and to be struggling. it’s just something that we’re kind of caught in and that this time could have an interesting effect on that. Like, what are artists supposed to do? I think the way that artists answered that question will be really interesting. Depending on how this all shakes out, could inform, what being an artist looks like the future.

Margaret Bullock: One of the things that I found interesting in the new deal that was unexpected to me, where these sort of artists migrations that groups of artists were moving. There’s quite a lot of movement back and forth depending on which projects we’re hiring or where there were places where you’re more likely to get work of the kind could do and things like that. And so there’s a real migration of important artists into the Northwest during that period of time. And I wonder in the aftermath if we’ll see something like that too. Like I know we’re fortunate here in the Northwest to have some really strong arts organizations and artists support and a lot of community interest , but there may be other States where that’s not true. I’m curious about why there, we’ll see that sort of migration again of artists kind of moving to places where they can still do the things they love and get support. though, of course, there’s all our other economic issues of how expensive it is to live here now.

Doug Detrick: we’ve covered so much, really interesting ground, and I really appreciate it, all of your time and sharing all of this expertise with us. It’s really fascinating. And congratulations on this book.

new deal art in the Northwest, the WPA and beyond. it’s a really beautiful hardcover book. tons of beautiful photographs and some great writing. we’ll put links up on the show page. For where folks can find it. thank you so much, Margaret.

Margaret Bullock: Oh and thank you. It’s been a real pleasure. I, I really get this much time to really get into the subject in depth and kind of think about it more broadly. So I really appreciate the conversation and the invitation. Um, and of course the plug for the book. That’s great. I’d love to people to read it. Now that it’s written and written, that’d be great.

And hopefully to, the exhibition that’s related, when we reopen our doors, it’s with us until August here in Tacoma, and then it’s going to go to the Halley Ford museum of art in Salem, Oregon. So, hopefully that all happens as we, as we plan and, people can see the exhibition as well.

Outro

Thanks so much Margaret. You can find a link to purchase the book on the episode page at moredevotedly.com. And if you haven’t already, please rate and review the show on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen. That helps new listeners find the show, and that makes me a happy podcast producer. And you can join the show’s email list at moredevotedly.com to see what events are coming up and to hear about new episode releases and other news.

My name is Douglas Detrick, and I produced this episode here in Portland, Oregon.

What you’re doing is beautiful. Can you do it more devotedly?